Great Red Spot, the

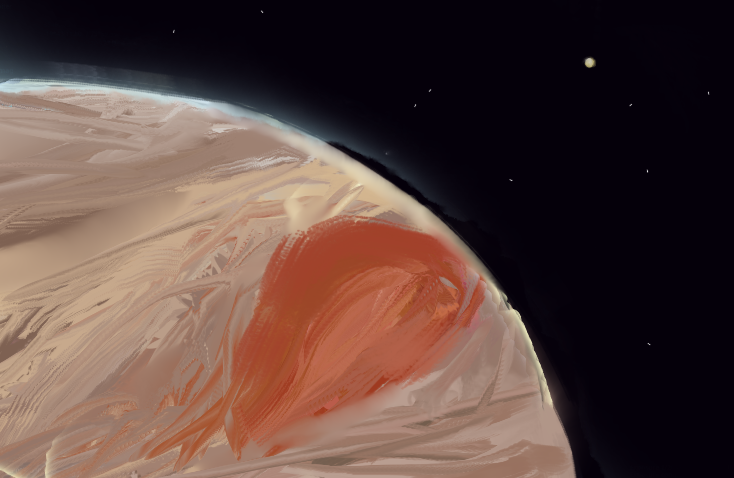

2558 CE The Great Red Spot, also known as Betelgeuse’s Eye, is a colossal artificial anticyclone located on Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. It and its natural predecessor have been an object of fascination since the invention of the telescope, and an inspiration for pilgrims and settlers since the early interplanetary age.

The size of the spot has varied over its history; the All-Jovian Zenoengineers’ Society (AZS) currently targets a diameter of fifty megametres, roughly four times that of Earth and ten times that of Ganymede. An array of sensors have recorded winds whipping past at up to 578 kph, significantly higher than anything measured during the spot’s original iteration, though a 2478 branch of the Jovian Journalverse1 attributes this to the scarcity of data prior to the 2200s.

The first spot

A storm meeting the description of a “great red spot” was first observed by Earthlings in 1665, fifty-some years after Galileo caught sight of his four eponymous moons. This incarnation of the storm arose by entirely natural processes, a swirling eddy born out of the chaotic dynamics of Jupiter’s thick atmosphere, and may have taken some years to rise to its most iconic form, as no astronomer would with certainty describe it as red until the 1830s.2

By the time of Pioneer 10, the first uncrewed probe, the spot had become a much-romanticised part of popular astronomical lore, second perhaps only to the rings of Saturn. It was around then, at the dusk of the twentieth century and the dawn of the twenty-first, that the first intellectual whispers of the Toynbeeite faith would coalesce.

It is often said that there were three types of colonists in the first wave of interplanetary migration: the scientists, the nutters, and the people with nowhere else left to go. The Toynbeeites, unremarkable as they seem today, fell definitively into the second camp. “Cryonics cult” was the byword used in Earthling tabloids of the day, and while the term “cult” does a disservice to their faith — a high-control group it is not, judging by the sheer amount of splinter sects — it proves applicable in describing their absolute determination to get to Jupiter and make it theirs.

The goal was simple: lug as many cryogenically frozen bodies to Jupiter as possible, knowing that somehow, some time, all the dead would be brought back to life. Precisely when was a matter of dispute. The more secular Toynbeeites saw the great resurrection as an ideal to strive for, rather than an ordained prophecy; they figured that it would be done when it was done, and science had figured it out. The more spiritual sects believed that the date of the resurrection was not for humanity to know. But in the squishy middle, the world of those who got degrees in biology but still prayed at their frozen forefathers’ chambers, one particular prediction was common knowledge: a date centred squarely on the Great Red Spot.

The Betelgeuse prophecy

Bowman wakes when Betelgeuse nods. Noöne knows with complete certainty where the ubiquitous saying originated; most Jovian historians of the era pinpoint its origin to Medici Station, but its earliest documented use is a 2074 graffito at the base of a Europan spacelift. Regardless of where it began, the word quickly spread all around Jupiter, practically accepted as deuterocanon by the mid-2080s.

Toynbeeite hermeneutics (read: “mental gymnastics”) being what it is, there were a range of cryptic interpretations, but the most common went something along the following lines. Bowman wakes would refer to the great resurrection of the frozen dead; a few tried to tie it in to the asteroid Chiron (“the bowman”)’s closest approach to Jupiter, but the 2001 interpretation was the more straightforward and the more familiar. Betelgeuse nods would most obviously refer to the star Betelgeuse, but it was a mere unfamiliar pinprick in the sky, and one whose demise by all reports wasn’t scheduled for another hundred thousand years. (Even in an age of effective immortality, a thousand centuries is a bloody long time!) So instead, the idea went, “Betelgeuse” must be referring to something else. Something closer to home. Rather than a great red star, perhaps a great red spot?

The spot had been on its way to “nodding off” for quite some time. A century on from Pioneer and Voyager, the storm had shrunk to half its past size, more a disappointing circular pimple than a commanding oblong fleck. Clearly, it was thought, when the spot finally dissipated and melted between Jove’s banded clouds, the time would come. Still, it felt like a stretch. As years turned to decades and no progress was made on revival, faith in the prophecy, and the Toynbee Idea as a whole, would wane.

Then Betelgeuse exploded.

The Great Solar Awakening, and the Great Jovian Disappointment

On April 11, 2120, Betelgeuse began to brighten in the night sky. By the end of the week, the distinguishing word “night” was no longer needed.

The cultural aftershock of this supernova, the closest and brightest in human history, was felt throughout the solar system; on Jupiter, its first wave came as a surge in religiosity. An idea many Jovians had dismissed as science fiction at best and a marketing stunt for a cryonics firm at worst had, over the course of a few nights, become all too real.

The explosion, of course, had failed to trigger the transhumanist rapture. Jim Morasco’s body sat as frozen as ever in his titanium coffin. But it was, surely, a harbinger of things to come. One eye of Betelgeuse had fallen, and now we just had to wait for the other to dissipate.

Off-world, Toynbeeite evangelists went into overdrive. Have you heard the good news?, they would shout, handing out leaflets and discount tickets to Europa; Millions now dead shall forever live! In the decade after, Jupiter nearly doubled its orbital population. Even for those not inclined to religious fervour, The Great Red Spot is dying — see it now before it’s gone! was a compelling reason to visit, and perhaps stay for the long haul.

In time, the spot continued to shrink. The rushing winds around it nibbled away at its russet hue, shrinking the spiral bit by bit. Every new year3, people toasted to another year nearer the revival of their ancestors — with the strongest vodka in the house, as was outer-system tradition.

The spot gave up the ghost at last in 2161. A generation on from the great nova, the wait was finally over. Children had been born, grown up, and had children of their own. Many of the Betelgeuse-born pilgrims had died and been put into waiting themselves. Now, as the last drop of red pigment smeared accross the clouds above, everyone around Jupiter could only hold their breath. Millions of families would be reunited. Thousands of artists and scientists taken too soon could continue their work. History itself would be delivered from the past tense.

Nothing happened.

Days passed. Still, nothing happened. Droplets of water condensed onto preservation tanks. Fêtes disappeared from calendars. Hour by hour, hope turned to disappointment.

This was not the end of Toynbeeism. The more secular faction had been toiling in the background for years, even as apocalyptic fervour swept the planet, and quickly reasserted themselves as the sort of people who would get the resurrection done themselves, not throw away forty years of potential progress because someone saw a snappy sentence on a wall. The true believers held out — some, in a state of trance, believed their ancestors had begun to cohabit their bodies, ushering in an era of transhuman mediums. Others believed the dead had been returned to life, but around Betelgeuse itself; a hundred or so truly devout spacers are still charting a course to the Betelgeuse Nebula today.

The second spot

As the Great Disappointment faded from memory, Jovians began to miss the spot. It was a comforting presence, as familiar as Selene in the Earthling sky. Without it, what was their world but a fat, unmarried Saturn? Around the system, even many who had never been to Jupiter felt the same. It was as if Earth had lost its forests, or Mars its valleys.

By 2180, terraforming was exiting the realm of uneasy experiments into that of established science. Aquiferous comets crashed down onto the Martian surface, sulphurous clouds cooled the Earth, and Venus was embroiled in a century-long holy war at the very thought. That year, the recently formed All-Jovian Zenoengineers’ Society — a coalition of smaller scientific groups which had previously guided the human body and the Galilean moons’ geology to meet at a happy middle — tepidly put out a call for ideas on how one might bring the Great Red Spot back to life.

Months of spirited debate and shouty virch-meetings later, a plan was decided. A network of solar shades and mirrors — designed by the same Martian firms responsible for warming their own homeworld — would blot out the Sun from a spot-sized patch of the Jovian atmosphere, while heating the rim around it. This would (fingers crossed) create a pressure differential between the two areas and (fingers very crossed) induce an anticyclonic storm the size of the original. Finally, once a storm had been cooked up, the clouds in the area would be seeded with tholins and iron particles, producing a red more vibrant than ever before.

Budgetary overflow aside, the decades-long plan went off without a hitch. The array of in-atmosphere sensors which kept the proto-spot in place during its formation birthed the technology which would later be used for Ouranos’s “atmohabs”, for the first time enabling people to truly live on a gas giant rather than around it.

The storm has persisted for centuries since, retaining its place as an interplanetary icon and symbol of the giant planet. Ganymedean authorities declared 2374 “the Year of the Great Red Spot”, organising various cultural events in its honour, including a well-renowned interactive play where the audience/actors are placed “in the situation room” on the day of the Great Disappointment.

Leave a comment