Manchester is not particularly renowned as a home for the aristocracy or patrons of the high arts, so i was pleased to discover upon a visit that the Manchester Art Gallery is one of the finest of its kind.

The Mag (as nobody calls it)’s success lies not in the size of its collection — it’s no larger than my local, the Laing — but in its presentation. Like many museums, its curators have lately been making efforts to diversify their collections and make them more relatable to the average yoof of today. It’s a process that can often come off as haphazard and rushed1, but the team at the Mag have pulled it off with care and respect.

Newer works are dotted in each gallery in such a way that they complement, rather than denigrate, the greats of old. A visa rejection letter from a group of Pakistani artists hangs alongside Victorian paintings of eastern caravans; where a gallery about protest and revolution could have added some shrewd, vapid letterpress and called it a day, the museum’s curators have instead chosen to incorporate a thoughtful self-portrait by a South African painter, made in the wake of the Marikana massacre.2

The captions accompanying each artwork face a similarly complicated task. Be too conservative and you’ll disappear up your own arse into a world of romanticist masturbation; be too reactionary and you’ll come off as cloyingly didactic, engaging in pseudohistoric iconoclasm for iconoclasm’s sake. The Mag hit a stroke of genius here: after a brief description in the typical style, the captions adorning prominent works also include conversations and thoughts from a variety of perspectives, be it historians, curators, or the artists themselves. It’s a brilliant way to further inform the visitor without beating them over the head with one opinion, alienating them with arcane academese, or leaving out unsavoury histories.

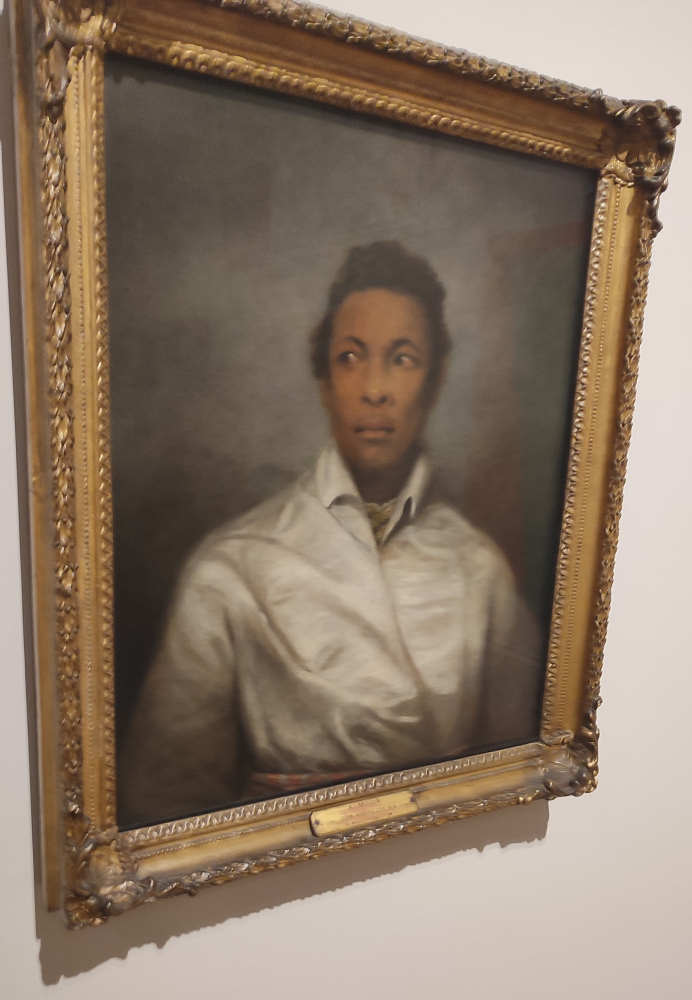

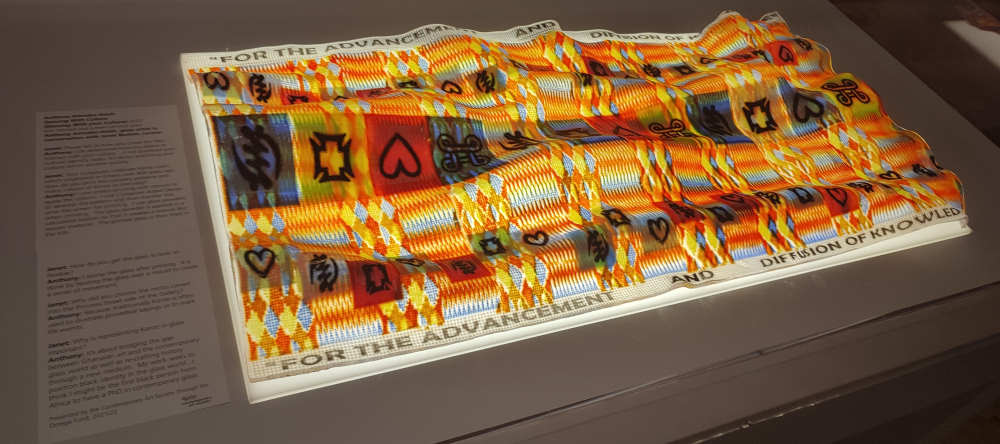

Other highlights on the lower floors include a portrait of the early black tragedian Ira Aldridge (the very first work in the museum’s collection, which rather surprised me coming from the people of 1858), a Ghanaian tapestry that i was surprised to learn was actually made of glass, and a lovely painting of an industrial scene lit by hazy fog whose name — to current me’s infuriation — i neglected to include in the photo, taken from an angle so inconvenient that reverse image search returns nothing of relevance. Past me is a bastard and i’m killing him when i get the chance.

Upstairs sit the gallery’s temporary exhibitions. The most prominently advertised was on the topic of the history of men’s fashion, something i regrettably could not get myself to muster up any interest in. I’m sure it’s quite interesting if that’s your sort of thing. The other (smaller) exhibition sits in a surprisingly grand hall which, from what i can tell, normally houses the museum’s pottery galleries, and it’s about tea. No wait come back i sw—

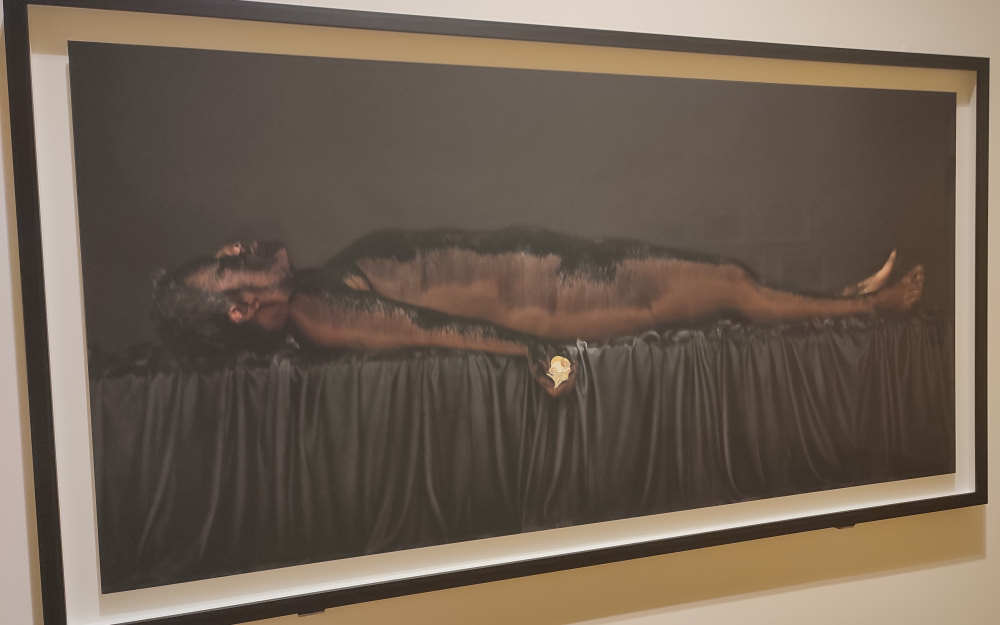

I jest, but there really is some fascinating stuff in there. The room’s cabinets are packed with advertisements, old jugs, and all sorts of other things detailing how hot drinks have shaped Britain and the world over the years — from sparking conversation to funding colonisation. But there was one thing that stuck out to me the most. A newly-created work of art, perhaps meant to inspire some thought or another in the viewer, but that our whole group agreed could only be described as one thing:

PS: I had to ask what the abbreviation “dbl” (“double”) on the signs for upcoming trams meant. My poor exurban soul simply could not comprehend the idea of a transit system that consistently ran so punctually — i had been thinking it stood for something like “delayed by late”.

PPS: This was meant to be the last post in the series, but my rambling about the gallery got so out of hand that i thought i’d spin off its intended complement into its own part. Tune in next week3 for one last dispatch from Affleck’s Palace.

Leave a comment