Periodisation, the splitting of history into neat ’n’ discrete temporal chunks, is a time-honoured matter of debate among historians. Where are the boundaries? Why are they where they are? Can periodisation even work in a global context?

Today, i will answer none of these questions, nor even attempt to seriously tackle the subject. For this is not a post about where the ages of man truly start and end. It is a post about how my brain reacts when it sees a year number and thinks “oh, yeah, that’s in… uh, that part of history”. What’s ancient? What’s mediæval? I dunno, but my subconscious sure does!

The Bronze Age(ish): c. 3500–776 BCE

The invention of writing is as good a time to start the clock on “history” as any, so circa 3500 BCE it is. It’s probably unfair to have a giant chunk of nearly three thousand years — as long as the entire rest of history — all by itself, split into nothing else, but when was the last time you saw an exact date in the negative four-figure range?

High Antiquity: 776 BCE–363 CE

This is the good stuff. I’ve chosen to start the clock not at the founding of Rome but at the (probably semi-mythical) date of the first Olympics, because Ancient Greece has always been cooler than Ancient Rome. (I can’t take a language where ⟨v⟩ is pronounced /w/ seriously.)

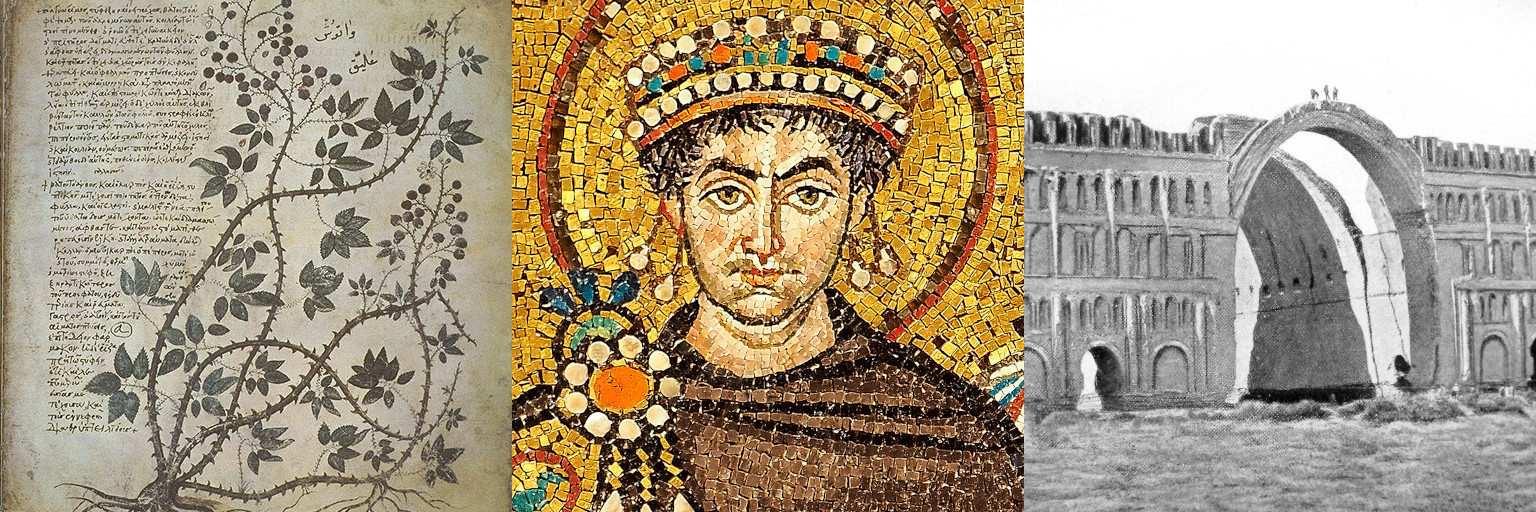

Weird amorphous transitional period: 363–622

I think most people generally have a decent idea of where the boundary between the Middle Ages and the modern day lies — somewhere around the end of the fifteenth century — but the line between antiquity and mediæval times has always been fuzzier, and i’ve never been sure where to draw it. After Julian died in 363, his successor was the last to rule over the empire undivided, the classical pagan relative tolerance of “anything but” giving way to the mediæval Christian doctrine of “nothing except”. It’s hard for me to fully accept what historians call “late antiquity” as firmly set in either era, so here it sits as its own weird little thing.

The Middle Ages: 622–1492

The rise of Islam as a conquering force cements in stone the end of any vestiges of the classical era; where Christians start their calendar at the birth of Jesus, Muslims have their epoch at the year that Muhammad and his followers fled Mecca for Medina, which seems a useful line in the sand.

The Colonial Age: 1492–1776

If ever there was a single date that parts The World Before and The World After, a horrible axis mundi on which history turns, Columbus’ arrival in America was it. Two parts of the world which had been isolated for millennia1 were suddenly, irreversibly welded together, bringing untold riches and untold destruction. So much was gained, and so much more was lost. Entire cultures were snuffed out in the pursuit of sugar, and from their ashes new ones grew. It’s hard to imagine what world we would live in without the Santa María.

The Industrial Age: 1776–1918

That’s not “1776” as in the American revolution, or even “1776” as in Adam Smith, but “1776” as in the year James Watt sold his first steam engine. At the start of this era, Manchester was a modest town of perhaps no more than fifty thousand people. By its end, it had ballooned to a heaving industrial city of seven hundred thousand. That about sums it up: for all the wealth made by colonial plunder, this was the age where humanity truly began to prosper.

The Postmodern Age: 1918–present

My natural impulse was to start our current age of history at 1945: the end of the war, the start of decolonisation, the thundering beginning of the atomic age… but, thinking about it, it’s all about what feels like history. I’m not sure me and someone from ancient Greece would have much in common to talk about — nor someone from mediæval France, or even Victorian London. But around the 1920s, a switch flips. They have cars. They have fridges. They have films, and radios, and fascists. I get the sense that a Paris cabaret girl and i share a society, a common world and ethos, in a way that people from before the war just didn’t. You could pluck her out of history and place her down in 2025 and, though she may be shocked at first, she’d adjust within the week. The interwar period is, to me, the beginning of “now”.

Leave a comment