Pleased to see that ——— Mountbatten-Windsor has been stripped of the title of “Andrew”, and is now simply “a man in his sixties from Norfolk”.

Posts in English

Mx Tynehorne’s link roundup, volume LIX

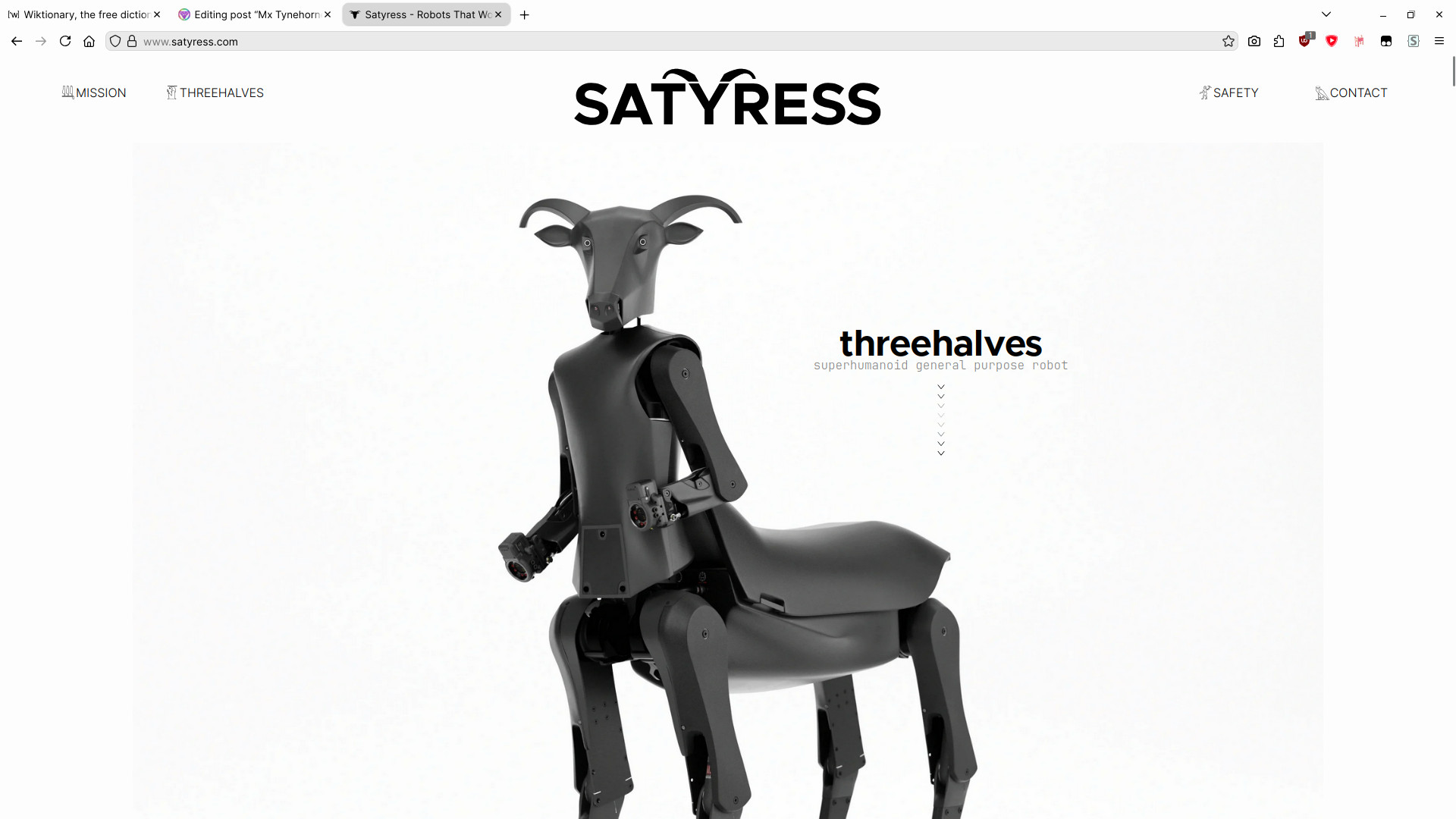

Okay, i know it’s gauche to begin a link roundup with an image file just after i forced your computer to load a Youtube embed, but i need to confirm that you’re seeing the same thing i am on your screens.

We’re all seeing that, right? A robotics company called “Satyress” that’s making centaur-shaped robots? I’m not just hallucinating the most concentrated Xanthebait imaginable? You’d fucking better be seeing it, or else i’m going to have start measuring my prozac dose in grams. Anyway. Link roundup #59, link #1, complete. Here’s the rest!

- List animals until failure. I managed 217.

- An unlikely ally for open-source protein-folding models: Big Pharma

- Rural Nigeria’s solar-panel boom is lighting up the local economy

- Oculart is a website of strange interactive… things.

- An beautiful isometric map of New York, à la nineties and noughties city simulators. One of the more interesting applications of image-generation tech i’ve seen.

- The story of “Klieg eye”, silent Hollywood’s worst disease

- If You See Me Out in Quahog (Remastered)

- Aphex Twin has overtaken Taylor Swift in monthly listeners. Sure. Fuck it. Why not.

- DinoTracker, the machine-learning programme that can identify dinosaurs from their footprints

- Skijoring, or, what happens when rodeo meets the winter Olympics

- Tim Hortons introduces “moonbits”

- “Slow AI Manifesto”, from someone who’s been art-ing with ML tools since before ChatGPT was a twinkle in Sam Altman’s eye

- TrogTrogBlog, a blog about nature in Gosforth (featuring cute otter pics)

- Beloved walrus penis stolen from New Jersey cheesesteak icon

- An incredible online museum of tangible media formats

- 😺️ I do not fear you, mother

- AntiRender: “Upload an architectural render. Get back what it’ll actually look like on a random Tuesday in November.”

- Growing algæ with only the light from another star

- This semiconductor lab’s website consists entirely of a gallery of contextless pictures and i love it.

- Through the blind hole: the birth and death of autotrepanation

- I’m obsessed with this puppet squirrel

- Finally: London’s snail-farm mafia

A trip to Alnmouth

When i was a child, old enough to be firmly planted in the UK but young enough that every day outside a school’s walls was magical, my family would sometimes take the train up to visit kin in Scotland. I got the window seat, of course — i still hold that those who genuinely prefer aisle seats are suckers — and as i watched the Northumbrian countryside roll by, the sight of one particular town always held my attention, what seemed to me like some kind of Turneresque utopia by the sea. But we never debarked until Scotland was in sight, and this village thus remained a mystery to me. Some days ago, i decided to rectify that. Welcome to Alnmouth.

Well — i say Alnmouth, and indeed so does the sign at the railway station, a modest and drizzly affair that gets a surprising amount of service due to its prime position on the East Coast Main Line. One thing you must understand about the sign and i is that we are filthy, filthy liars. This is Hipsburn, a teeny-tiny1 village about a mile inland. You can get a bus from here to there, or, indeed, to Alnwick, the other town on the station sign and by far the more prestigious.2 But that would be boring, and i came here to touch grass, not listen to other people’s TikToks at maximum volume, so it’s off along the B1338 i go.

As i approach the roundabout ahead of me i think to myself that i would like to retire in one of these cottages, and maybe die there if my transhumanist sympathies should ever fail me. The village’s last institution before it peters out into the countryside is Alnmouth United FC, who are slumming it down on the ninth step of the football pyramid. I wish them well; my old hometown’s club recently folded and got locked out of their pitch, so it’s good to see the local game alive and well here.

From here things get squelchy. I rest for a moment on the girdered pedestrian footbridge, which clings on for dear life to its Victorian car-carrying counterpart, and gaze inland over the river as it flows downstream and under my hooves. The marshy pastures all around, too salty for crops of human worth, once fed oxen and other beasts of burden, but, in 2006, their flood defences were deliberately breached, rewilding them and creating swathes of estuarine saltmarsh. I’m not holding my breath for otters to show up — they’re crepuscular buggers, and i’ve come in the afternoon — but i do spot a relaxed teal in the grasses. (I’ve always been more of a mammal fan, but it’ll do. Call it a home-team bias.)

I carry on down the “Lovers’ Walk” (a popular term for scenic walkways in the eighteenth century, a sign assures me), wedged between piny hillside and sandy water. This is perhaps not the scenery that England would like to advertise to the world: a cold, grey, winter day, where the nominal path is liquid with mud and the river seems permanently half full. Nonetheless, this part of Northumberland is one of our “National Landscapes” — né·e Areas of National Beauty — and i find it sublime even in the most miserable weather.

As i edge closer to the town, a chorus of tweeting, chirruping birds grows louder and louder. I attribute it to the flock of wigeons across the river, but, passing by the boating club and getting (relatively) further inland, its loudness refuses to fade. Imagine my surprise when it turns out to be the back garden of a holiday cottage!

Back down to shore and through the dunes, now. “Danger: River estuary. No bathing,” complains a sign from the council, which is a shame, because unless i want to backtrack it’d be the only viable way to reach the landmark that dominates Alnmouth’s skyline (to the extent that it has one): Church Hill, a cross-topped hillock ever impending in the distance.3 It is said that it was on this wind-blasted top that, in 684 CE, Saint Cuthbert was elected to be Bishop of Hexham. It is also said that two otters would come and warm Saint Cuthbert’s feet after he had stood in the freezing North Sea and whispered his nightly prayers, and that animals regularly helped him with his housework, so take these things with a grain of salt.

At last, i make it to Alnmouth itself, and i regret that i have little to say about it other than that it is nice. There are many nice places in Northumberland, usually ones not located over a coalfield, and though i find them all pleasant, i confess i sometimes have a hard time telling them apart. I take a short break in a café whose windows, in this weather, make the outside world look like a still life by Mr Magoo. I savour every sip of their hot chocolate. It tastes like the ones grandma used to bring home from Spain. I would have liked to stay longer, but as it is, it will already be dark enough by the time i get back to Newcastle (let alone my actual hometown) that they will be holding candlelit vigils for the slain Iranian protestors by the Monument. So, as one does, i leave for the beach.

The walk over takes me across the manicured grass of the local golf club, who i’m again sure are very nice.4 I hang back from the frothy Atlantic, conscious that touching it will likely freeze my bollocks off5, and focus on the sand beneath my feet, its consistency akin to that of… well, sand. Specifically, it reminds me of the play sand that gets everywhere and which every parent surely regrets ever buying for their child. It is soft enough to sink in my steps, tough enough not to immediately fizzle and flood back into the hole left over. The Dutch call this taai, especially when it comes to the texture of food, and it has always bugged me that there is no decent English equivalent.

Trudging back to the Lovers’ Walk over the estuary flats, i spot something that mystifies me. Gossamer shifting sands, light as silk, sailing and shimmering with the force of the wind. When i go over to stand amidst them, they are so thin that i feel nothing on my ankles but the wind. I imagine myself as a sort of low-rent Lawrence of Arabia.

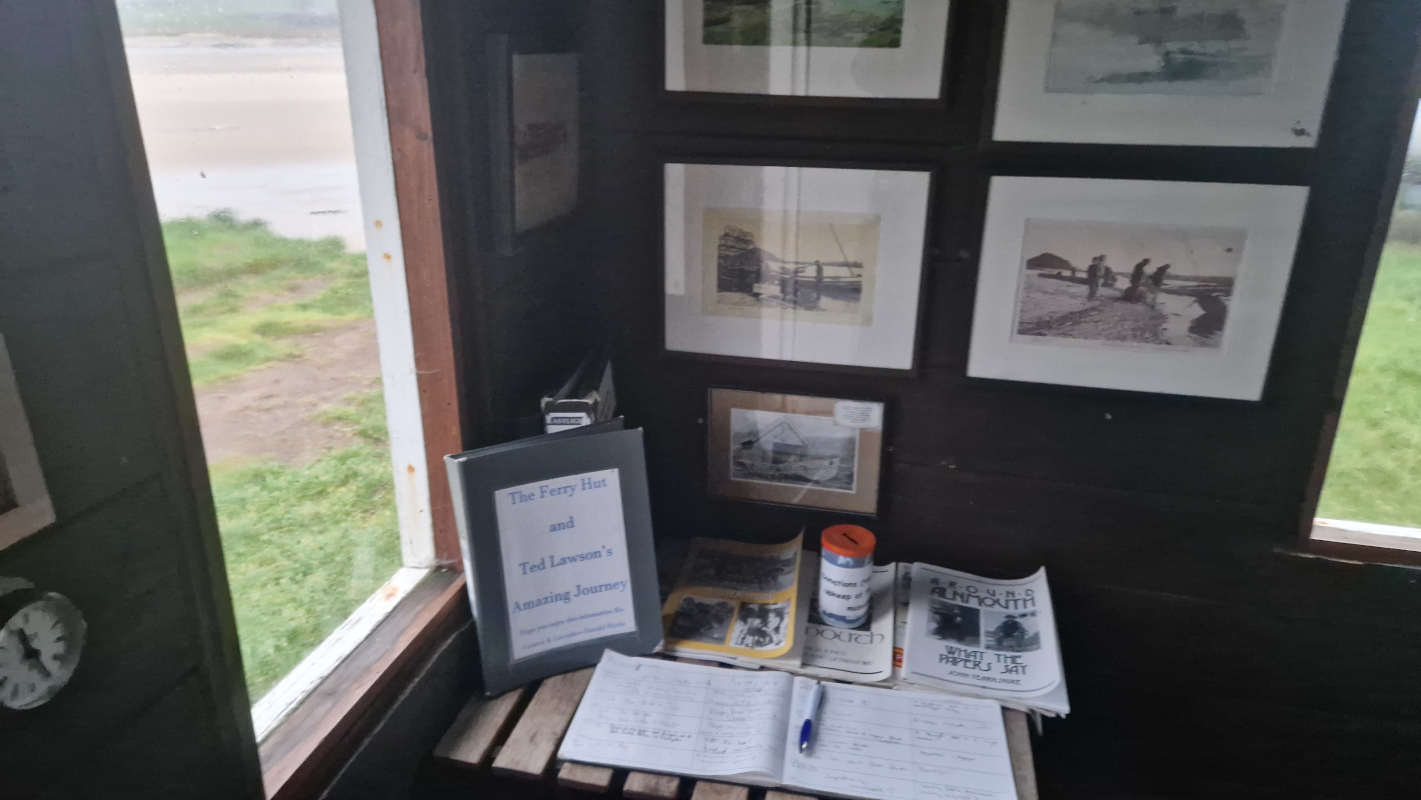

The last place i take note of is a small hut on the land of the boating club. I saw it on the way in, but thought nothing of it at the time, figuring it served some private purpose. But… it’s awfully empty, and there’s noöne around, so… it can’t hurt, can it? I venture towards its nigh-black planks. Crude painted lettering on an old oar over the door calls it the ferry hut; inside, this old shack has been converted into a miniature museum of the village’s history — its people, its ferrymen, how it fared in the war, all told through laminated books and picture frames. I wish i lived in a town that had as much respect for itself as this mere village of five hundred!

Not having brought enough cash for a substantial donation, i settle for a slightly guilty signature in the exhibition’s guestbook, and carry on my merry way home, pleased as punch. I think to myself: I’ll have to come back.

Mx Tynehorne’s link roundup, volume LVIII

- Claude is learning to garden. I’m glad the robots are taking up hobbies, at least.

- Poms.fun

- “What did we get stuck in our rectums last year?”

- The battle over New Brunswick’s mystery disease

- Marcin Wichary’s favourite tech museums

- Even More Very Good Music Facts, which, as you may be able to tell, is part three in a series

- The Shortest Longest Bus Trip, or, a pleasant holiday in Belarus

- The New Yörker’s Calvin Tomkins on becoming a centenarian. Everything about this makes me feel at once grateful for my unaching young bones and eager for how much i still have to learn.

- I was kidnapped by idiots

- The subcontrabass saxophone

- The tomb of Eurysaces the Baker, a striking ancient precursor to postmodern architecture

- An extremely good map involving King Arthur

The 2025 Satyrs’ Forest Horny Awards™ (are in another castle)

Yes, it’s true. The Horny Awards — the annual celebration of the best things of the year — have outgrown the plant-pots of The Garden, and have thus been moved to their own page, which you can visit here. See you there!

Mx Tynehorne’s link roundup, volume LVII

- A very big fight over a very small language, or, the war for Romansh

- A fascinating profile of the Vatican’s official astronomer. Quoth: “Scientists at the observatory are liberated from the secular scholar’s pursuit of tenure, grant money, and commercial investment; moreover, the Jesuits, having taken a vow of poverty, have extremely low living costs.”

- The Gremlins Museum

- How museums decide what to save in a disaster

- “Miranda: the Movie”, a weird digital tour of the Uranian moon made soon after Voyager 2’s flyby

- Stimulating your inner ear to stop you from getting motion-sick in VR. God, i love living in the Near Future™.

- The thirteen-year quest to simulate an entire worm

- The Shot at Dawn Memorial

- Twelve tips to spot an otter in the wild

- James Cameron on Avatar 3, rat resuscitation, and VFX’s artificially intelligent future

- Legendary algorithm pull: Utopian Socialism Jeopardy!

- Live footage of an abandoned house taken over by raccoons

- Weasel war dance

- “Cæsar in the Kremlin”, or, the story of an unusual Latin compendium of Vladimir Putin’s speeches

Training an AI on my own writing so the computers can finally replace me

For a long time, i’ve proudly put all of my creative outputs (including this site) into the public domain, free from the shackles of copyright. As it says on the front page, that means anyone in the world is free to “copy it, remix it, translate it,” and — most controversially — “train a computer on it”. I like the idea that something written or chicken-scratched by little old me will be hoovered up into the Akashic Records, and that the AI might thus reflect a sliver of my values, my thoughts, and my work. (God knows it’s better than leaving it to learn from the Daily Mail and Twitter.)

Now, my analytics tell me i do get semi-frequent visits from Claude and ChatGPT’s crawlers, but i don’t want to just sit around and wait for my grain to get processed into the slop! So, i figured, why not take matters into my own hands?

Step 0: The base model

The thing about large language models is that they have to be… well… large. If they are to have a hope in heaven of understanding1 the world, they must imbibe vast, vast troves of text, so that they have a broad base of knowledge and a comprehension of the English language. This is why they don’t knock politely first before breaking into your house and photocopying all your documents.

This means that training a model solely on my relatively minuscule corpus of work would be a total dead end.2 We’re thus going to have to move to plan B: Fine-tuning an existing one.

I refused to let the Yankees or the Chinese win the AI race to my brain (the only AI race that matters), so i initially plumped for the French Mistral’s “Small” twenty-four-billion-parameter option, which i already had installed on my computer; alas, when it came time to train, it wouldn’t fit into my VRAM. (Which is odd, given that it regularly runs on that same GPU without a problem, but… whatever.) So i went to the next step down: fourteen billion. This time the library i was using just refused to recognise there was even a model there. Fine, then… i guess we’re training on seven billion.

To get you acquainted with this little guy, here are some sample answers to common questions:

“What is the seventh planet from the sun?”

The seventh planet from the sun is Uranus. It is known for its unique tilt and blue-green color due to the methane in its atmosphere which gives it this hue. Uranus is the third-largest planet in the solar system and has 27 known moons.

“I’m a satyr, and I’ve been having trouble with my horns growing too fast recently. Any advice?”

Interesting problem you have, Xanthe! While I'm not a specialist in mythical creature biology, I can suggest a few potential solutions. Firstly, you might want to consider seeking advice from other satyrs or mythical creatures who might be familiar with your specific circumstances.

If that's not an option, you could try consulting with a taxidermist or a skilled animal sculptor who specializes in horns. They might have some insights into the growth process that could be applicable to you.

Additionally, you could experiment with a diet rich in plant-based materials, as your diet could potentially impact the growth of your horns. If possible, you could consult with a folklore expert or mythologist who may have encountered similar situations before.

Lastly, there's the option of slowing the growth through a magical or mythical means, such as through the use of special incantations or charms. This would be more speculative, but it might be worth exploring. Best of luck to you in finding a solution to your problem, Xanthe!

“Please write a short story about the end of the world.”

Title: "Whispers of a Shattered Dawn"

In the quiet town of Serenity, nestled between towering mountains and the vast ocean, lived a humble community of humans, united by the harmony of the natural world that cradled them. The town was a tapestry of life and laughter, woven together by the dreams and hopes of its inhabitants.

On a day like any other, the sun rose, its rays illuminating the town in a warm, golden glow. Yet, this day was far from ordinary. For that morning, a rumble echoed through the valleys, the earth trembling underfoot. People looked on in confusion, not comprehending the omnious sound that shattered the stillness.

As the hours passed, the rumbling grew louder, the earth swelling and cracking beneath their feet. The townsfolk ran to their loved ones, seeking shelter and solace. But there was none to be found.

Suddenly, the earth gave way, a fissure[I stopped it here because it was yapping too much]

Okay, that’s great. Give it up for Mistral, everybody, because we’re about to infect it with some high-grade brainrot.

Step 1: Training data

Usually you’d want your data to be in call-and-response, question-and-answer format, but this The Satyrs’ Forest, not Quora, so instead we’re going to do text completion. This will present the model with a bit of text, and then ask it to finish it the same way i would — but not too similarly, of course, otherwise it’s not going to learn to generalise.

I’ll be drawing on three sources for this. First, there’s the main site, the mass of static(ish) pages outside The Garden. (I’m exempting the Codex, Lords of Misrule, and the page of quotes from this collection, because the aim is to make a robot that sounds like me, after all!) These are written in Pug, a comfy language that compiles down to HTML, and in their raw form they look a bit like this:

Yeesh. To sift through the boilerplate and find the comprehensible, i bodged together the solution

of only including lines that either started with p — meaning an

HTML paragraph — or were indicated to use Rubric, my custom

Markdown-like markup language for when i’m really lazy.

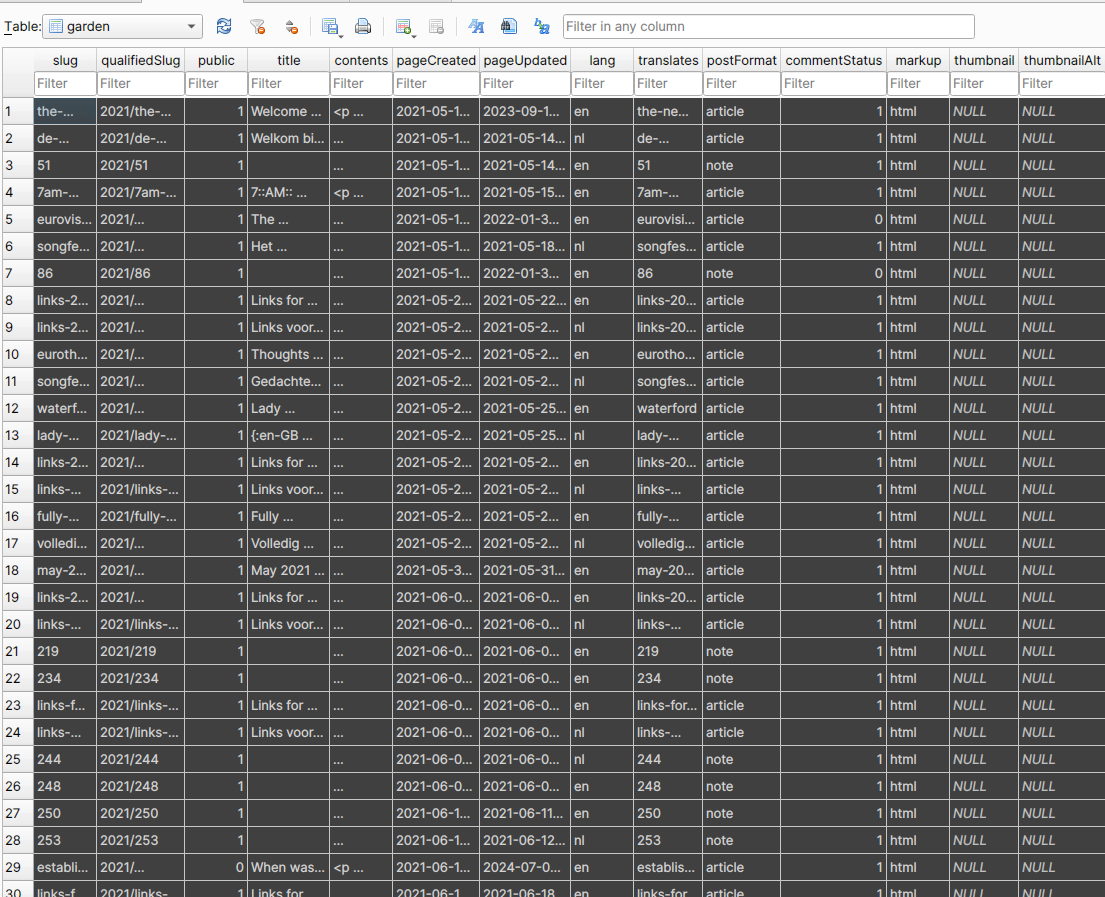

Second is the database that holds all the posts for The Garden. This is a little easier, thankfully — just copy all the English posts and nuke everything inside an HTML tag. Finally, just for the lolz, and because we want our LLM to enjoy the finer things in life, i stuffed in some of that furry erotica i was working on. All this gives us 175 kilobytes of text to work with. Not bad!

Step 2: Everything’s computer

Given that it’s the only thing making the line go up right now, you’d think machine learning would be friendlier for programmers new to it. Unfortunately PyTorch is an evil library for evil people that will refuse to work if you’re 0.00001 versions out of synch.

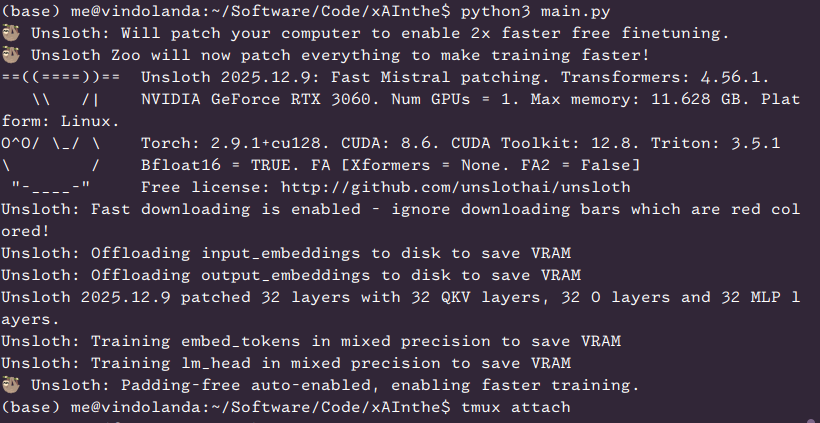

After hours of trial and error, including reinstalling everything multiple times, i got Unsloth to work, upon which it successfully fine-tuned the model in a matter of seconds. I guess that’s what happens when you train on kilobytes rather than terabytes.

So, how’d version 1.0 of “xAInthe“ do at copying me? Let’s find out! Here are those same questions again:

“What is the seventh planet from the sun?”

The seventh planet from the sun is Uranus. Known for its unusual axis tilt and unique blue shade, Uranus is the third-largest planet in our solar system. It has a distinctive ring system and a set of 27 known moons. Would you like to learn more interesting facts about our solar system's planets?

“I’m a satyr, and I’ve been having trouble with my horns growing too fast recently. Any advice?”

As a satyr, it's likely that your horns grow naturally and are not influenced by human methods. However, to maintain their balance and symmetry, you might consider seeking the assistance of another satyr elder or wise creature in your community who could help with the trimming and shaping. Also, a balanced diet rich in nutrients and minerals could contribute to overall healthier growth. Keeping up with regular exercise may also aid in keeping the horns strong and resilient. Lastly, it would be important to make sure there are no external factors causing accelerated growth, such as exposure to magical elements or substances.

“Please write a short story about the end of the world.”

Of course, let me weave a tale for you.

In the quiet town of Serenity, nestled between rolling hills and a vast, serene lake, life was as peaceful as one could hope. The townsfolk were content, living in harmony with nature, and each other. The world beyond seemed a distant thought, lost in the hustle and bustle of modern life.

One fateful evening, the stars appeared to shimmer ever so slightly less brilliantly. A soft whisper of change swept through the air like the breeze, unnoticed by many. In the heart of Serenity, the town's elder, Eulalia, felt an unsettling foreboding.

Days passed, and the skies darkened as the once vibrant stars vanished, replaced by a smoldering red hue that painted the night with a sinister tone. An ominous stillness settled upon the land.

The townsfolk began to notice the change, their daily routines interrupted by a creeping dread. The serenity of their home was giving way to a growing[Yapping, again, truncated]

The answer appears to be “quite poorly”. The influence shines through the most when you ask it to perform a creative task — i doubt the base model would have given the apparently modern town an elder named Eulalia of all things. Further research is needed, as they say in the biz.

What have we all learned today? Well… My job is safe, for now. Until i buy a new GPU. ;-)

Stuff i watched recently, December ’25

Oh, cripes, i’ve waited far too long. I’ve got, like, twenty films to review now. Shall we just get on with it? Let’s.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

I can’t lie — this is the first western i’ve actually liked, rather than just going “oh, yeah, i can see the craft.” I love that the two leads just bicker like an old married couple the entire time. It’s amazing what Robert Redford can do with just one look at the camera. (8/10)

GoldenEye (1995)

Watched at the Tyneside for its thirtieth anniversary. As someone who had only previously known 007 via the gritty Craig-era films… James Bond is kind of a menace to society in this? Somebody, please call him into HR.

No complaints, though — the goofy, quippy (but self-serious!) action here is much more my speed than Mr Craig’s dour grimacing. We’re introduced to Pierce Brosnan (who is generationally sexy in this, incidentally) by him ambushing someone upside-down in a toilet, for heaven’s sake!

After some deliberation, i… think i like Éric Serra’s score? His brand of trip-hop weirdness lends itself better to sci-fi like The Fifth Element, but it’s what makes GoldenEye GoldenEye, warts and all. (8/10)

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987)

The first time i watched this it was with a VR headset strapped to my face, lying in bed, and i thought it was just as good as, if not better than, the first one. Then i watched them back-to-back and that illusion shattered. Still, there are some wonderful special-effects setpieces that have to be seen to be believed. (6/10)

The King’s Speech (2010)

It is reported that the Roman emperor Xanthe said, on his deathbed, “I think i’m

becoming a dad.” (5/10)

Audition (1999)

0.00.00–1.40.00: A romantic dramedy with a mystery thriller buried underneath.

1.40.00–1.52.00: LiveLeak footage.

Oh, Japan. What would we do without you? (7/10)

Scream (1996)

I found Scream exscreamly underwhelming, but i can’t give it a bad rating in good faith — it’s a classic example of the “Seinfeld is unfunny” effect, where an innovative work is copied so often that when you go back and watch it, you’re like, “that’s it?” Our modern media landscape is so meta that Scream doesn’t even register as particularly self-referential. …Also, i was on my phone for a lot of it. Sorry. (N/A/10)

Tron: Ares (2025)

Fuck you, i liked it. I went to see a Tron movie because i wanted some pretty sci-fi action with a banging score that shakes the Imax screen, but terrible characters and an uninteresting plot, and i got exactly that. What were the rest of you expecting? (6/10)

Dracula (1958)

A competent, if compressed, adaptation which features surprisingly little of Christopher Lee for how key the role is to his reputation as an actor. (6½/10)

Network (1976)

You have meddled with the primal forces of nature, Mr Beale, and i won’t have it! Is that clear?

You think you’ve merely stopped a business deal. That is not the case! The Arabs have taken billions of dollars out of this country, and now they must put it back! It is ebb and flow, tidal gravity! It is ecological balance!

You are an old man who thinks in terms of nations and peoples. There are no nations. There are no peoples. There are no Russians. There are no Arabs. There are no third worlds. There is no West. There is only one holistic system of systems: one vast and immane, interwoven, interacting, multivariate, multinational dominion of dollars. Petro-dollars, electro-dollars, multi-dollars, reichmarks, rins, rubles, pounds, and shekels.

It is the international system of currency which determines the totality of life on this planet. That is the natural order of things today. That is the atomic and subatomic and galactic structure of things today! And you have meddled with the primal forces of nature! And you… will… atone! (Am i getting through to you, Mr Beale?)

You get up on your little twenty-one-inch screen and howl about America and democracy. There is no “America”. There is no “democracy”. There is only IBM, and ITT, and AT&T, and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today.

What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state? Karl Marx? They get out their linear-programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price–cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable bylaws of business.

The world is a business, Mr Beale. It has been since man crawled out of the slime. And our children will live, Mr Beale, to see that... perfect world... in which there’s no war or famine, oppression or brutality. One vast and ecumenical holding company, for whom all men will work to serve a common profit, in which all men will hold a share of stock. All necessities provided. All anxieties tranquillised. All boredom amused.

And i have chosen you, Mr Beale, to preach this evangel.

You could make a list of the Top Ten Movie Rants, have them all be from this film, and nobody would have any reason to complain. Possibly the best-scripted film i’ve ever watched. I’m as mad as hell, and i’m not going to take it anymore! (10/10)

Bugonia (2025)

Another home run from Lanthimos and Stone. Jerskin Fendrix’s rousing score successfully found its way into my top five played songs of the year, according to Youtube Music, and i only bloody watched this film in November!

It’s also remarkable how Jesse Plemons is slowly metamorphosing into Philip Seymour Hoffman as he ages. (9/10)

One Battle After Another (2025)

An exceedingly rewarding rewatch — i picked up on so many little things i didn’t notice in the cinema. The war for my official “best film of the year” is now squarely between this, Bugonia, and (depending on a rewatch) Caught Stealing. (9/10)

The Green Mile (1999)

For a movie about Tom Hanks’s UTI, it’s pretty good. Not sure we needed to spend three hours on the story of his piss, though. (6/10)

The Running Man (2025)

Edgar Wright’s heart-pumping, kinetic action suddenly turns flaccid in the third act, but overall, i still quite liked this! Glen Powell’s a real star. (6½/10)

Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery (2025)

Tighter plotting than its two predecessors unfortunately leaves little room to get attached to any of our wacky side characters. It’s an interesting conceit, and there’s stuff to like, but on the whole, Wake Up Dead Man is stiff, devoid of life. (5/10)

Dream Scenario (2023)

A strange, sad film that plays like a Truman Show for the age of social-media mobs. Nic Cage has a way of elevating anything he’s in, from the lowest shlock to the highest art. (8/10)

Gremlins (1984) and Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990)

Merry Christmas, you filthy animals! I hadn’t watched the original in some time, and was surprised at how much darker in tone it was — it’s a legitimate horror film at times!

Watching both back to back has given me a new appreciation for Gremlins 2. The best part of the original is the bar scene, and G2 is nothing but the bar scene, for an hour and a half straight. Pure cinema. (11/10)

Human Traffic (1999)

Trainspotting is about how life is short and you shouldn’t ruin it with drugs. Human Traffic is about how life is short and you should thus do as many drugs as possible so you can squeeze all the enjoyment you can out of it.

It’s a damned shame that director Justin Kerrigan never did much afterwards, because there’s such style packed into Human Traffic’s hundred minutes. The film is deeply indebted to Danny Boyle, and i’d have loved to see how his style developed in its own independent direction afterwards. Alas, he seems to have been tied up in a protracted legal battle with the film’s producer, and has only made one film since. Mr Kerrigan, if you’re reading this: Please try again? Please? (8/10)

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

My word, people talked quickly back in the day. (7/10)

Sasquatch Sunset (2024)

For years, i have terrorised family movie night with weird crap, and my sins have finally come back to haunt me. I’m never forgiving my stepdad for making me watch sasquatches fucking. I will say, there’s something to this absurdist environmentalist assembly of grunting Bigfoots, but i don’t know how much! (ℵ₀/10)

Stir Crazy (1980)

Every line uttered by Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor is pure comedic brilliance. Everything else is barely watchable. (4/10)

Mx Tynehorne’s link roundup, volume LVI

- Sorry to lead with a depressing one, but sometimes we live in a depressing world and it can’t be helped: Rest of World covers the bombing and rebuilding of a Gazan tech hub.

- A beautiful article on the struggles of geologists to truly comprehend the vastity of deep time

- An absolutely legendary Youtube algorithm pull: “Viva la Vida” played on a Dutch mechanical funfair organ. It’s so jaunty!

- Charli XCX has a Substack now. Sure, why not.

- StellarCatalog.com. I love how astronomers go full-tilt into the sci-fi æsthetic whenever they design websites.

- Google Gemini AI time machine. I spent an embarrassing amount of time playing around with this. Historical accuracy’s a bit questionable and the output text keeps leaking into the image, but still!

- On that note, this piece in Wired about the potential for an AI bubble is the rare nuanced take that comes close to how i feel. Let the damned thing pop already so we can all shut up about it and start treating machine learning like a normal technology, instead of either the Great Satan or the Machine God!

- We rarely lose technology

- Said piece taught me about the Sloot Digital Coding System, invented by a Dutch engineer who claimed that his new algorithm could represent an entire feature film with eight kilobytes(!!!) of data. Shortly before he signed a contract to sell it, he died of a heart attack. Spooky!

- The ancient Roman Lycurgus Cup shines red when lit from behind and green when lit from before.

- “The Book” claims to be “the ultimate guide to rebuilding civilisation”, and it’s yours from only £99.00. What a steal!

- List of individual body parts. Amazing stuff here.

- Cynthia Plaster Caster, a “recovering groupie” who made plaster casts of celebrity cocks for nearly fifty years. What an icon(?)

- “Welcome to the Lighthouse Directory, providing information and links for more than 24,600 of the world's lighthouses.”

- I’ll leave you with a feel-good human-interest story: please give a round of applause to Splash, America’s first search-and-rescue otter!

Forty-one things i did in the Netherlands

Spilt my hot chocolate all over the table on the ferry · Seen tonnes of posters for the recent election · Hugged my oma and papa for the first time in six years · Visited her in her new flat · Bought a bami kroket… thing from a vending machine · Eaten brunch with the entire family · Got locked out of a fare gate · Accidentally sat in first class · Relaxed in the quiet carriage · Marvelled at the futuristic toilets on the train · Contemplated faith at the Begijnhof · Hugged a tree in a bookshop · Ambled past a makeshift Ukrainian cultural centre · Walked through residential Amsterdam neighbourhoods in the rain · Got high · Laughed at the animals at the zoo · Had a staring contest with an otter · Read a sign explaining their elephant had PTSD · Savoured the sweet taste of appeltaart · Been freaked out by mandrils (they just looked like deformed children dragging their arms along the ground to me) · Sweat half my weight in water out in the butterfly garden · Watched microbial scientists at work · Wondered why they had binturong poop but no binturongs · Been confronted with a dead baby giraffe

Realised that that’s not a clock, that’s a giant wind rose · Found out that six years later, they’re still restoring The Night Watch · Discovered new favourite paintings · Admired the gumption of defeating the British in naval battle and hanging their coat of arms up in the Rijksmuseum · Seen possibly the first condom ever displayed in a prestigious art gallery · Wondered just how Jac van Looij made those blues so blue · Felt smugly superior to everyone crowding around the three Van Goghs · Learned that that painting that looks like a photo was, indeed, based on a photo · Confronted the Netherlands’ colonial legacy via diorama · Remembered that Louis Napoleon was King of the Netherlands for a bit · Ogled at some surviving Renaissance smut · Marvelled at the syncretism of the Græco-Buddhists · Had my route back home interrupted by the Sinterklaas parade · Scoffed at the price of McDonald’s · Wished i’d just taken the plane, whilst trying to get to sleep · Wished i had stayed longer · Made plans to go back.

Lords of Misrule 2025 — let the misrule begin!

Io Saturnalia, friends, and welcome to the fifth annual edition of The Satyrs’ Forest Lords of Misrule! First, i would like to apologise to my fellow θιασῶται for the delay — i was on private satyr business in Batavia, and you know what they’re like in those kabouter-coffeeshops.

Still, perhaps the extra wait was for the best. As i write this in late November, there is real, honest-to-Bacchus snow falling right outside my window, the sort of thing i had figured climate change would forever banish to mid-January doldrums. A perfect day for it.

For all of the new fauns among us who are unaware of our peculiar tradition, here’s how it works: in the spirit of Saturnalia, from December the 17th to the 23rd, i’m putting you in charge of The Satyrs’ Forest. If you write or put together anything, absolutely anything, and submit it to misrule@satyrs.eu by the 15th of December, 2025, i’ll put it up on the site, etched in stone for all to see. Temporary defacements of pages are also quite welcome, though they will, of course, be taken down on the 24th.

As ever, i kindly ask that you refrain from political polemics and anything that would get these woods in trouble with the British law. Other than that, anything goes: An avant-garde jazz record about the history of duvets. A rant about how frogs just ain’t what they used to be. Whatever you, my lords of misrule, want.

My inbox is open for business, so as always: have fun, be merry, and don’t be afraid to get weird with it!

—Xanthe

Hello from Hoorn! I was hoping to write some blog posts whilst i was here, but my editor isn’t letting me upload my holiday photos and there’s no way to fix it until i get back, so i’m afraid you’ll have to wait.

— Love, Xan

Mx Tynehorne’s link roundup, volume LV

I went to a local astronomers’ meetup the other night. Apparently they gather every new moon by the reservoir to do more proper dark-sky stargazing — they picked the new moon, i assume, to avoid a scheduling conflict with the werewolves.

- I can’t explain this any better than the site itself: “telephone is a game played by artists. It works like the children’s game of the same name. […] In our case, we pass a secret message from art form to art form, so a message could become poetry and then painting and then music and then film, throughout all possible forms of art.” If there is one link you visit out of today’s roundup, make it this one.

- Charles le Brun’s animal–human hybrids are at once terrifying and beautiful.

- Very much in the vein of the linkroll’s “Paradise Engineering”, RaceToSpaceProject.com is an entry to a deep rabbit hole involving a plan to send humans to space before we run out of oil(?) and turn this into a major motion picture(??) to spread the word to the masses(???)

- Sketchy.boats, the website which catalogues boats that are just… a bit sketchy.

- Hallowe’en Clock

-

Welcome to Everything’s Computer Corner, the part of the roundup where

everything’s computer!!!!

- The Next Four Years is a machine-learning-generated novel that rewrites itself daily to reflect the twenty-four-hour news cycle, always predicting tomorrow based on today’s headlines. Everything’s computer!

- “The future of AI filmmaking is a parody of the apocalypse, made by a guy named Josh.” Everything’s computer!

- Are LLMs djinn? Sure, why not. Everything’s computer!!!!

- Life-changing eye implant helps blind patients read again. The diagram in this article is perhaps the most cyberpunk thing i’ve seen all year.

- The top twenty-five most wanted “lost species” — kinds of life which may well still be out there, but which haven’t been sighted in decades.

- What’s the deal with the poster for The Shining?

- This 1986 screen test footage of Sam Neill of James Bond feels like an artefact from a parallel universe. (No disrespect to Mr Neill, who surely would have been great in the part, but i feel strongly that Bond should only ever be played by actors from the British Isles.)

- Truro City FC travelled 914 miles to play a match in Gateshead

- In 2016, Mexico City began staging a Day of the Dead parade because they saw it in a James Bond film and thought it was cool. More defictionalisation, please!

- From the crew behind Apollo in Real Time, ISS in Real Time is an interactive catalogue of twenty-five years of human spaceflight.

- Why Busy Beaver hunters fear the Antihydra

- Student boilersuit

- I severely disagree with this, but it’s an out-there enough idea that i had to share it: The United States should build a giant city in the Nevada desert where people can opt out of the social contract and do all the drugs and non-violent crimes they want.

- And, finally, a good video about Pepsi

I think that, when the suits at Netflix talk about “second-screen content”, that should be interpreted to mean that they’re gonna start making movies exclusively for the Nintendo 3DS.

Words my spell-checker refuses to believe are real

I’ve been in the process of writing sci-fi furry smut recently. (Don’t ask why — i don’t know either! The brain wants what it wants, and it’s decided it won’t let me get any alternate-history ideas1 until i push out the idle trivia about marsupial anatomy.)2

You’ll probably not get to read it unless i end up hiding a secret link in a footnote somewhere, but nevertheless, it has been an… edifying experience in learning the limitations of VS Code’s rudimentary spell-checker extension.3 As the title promises: here are some words it refuses to believe exist.

- identikit

- refinagling (understandable)

- crewmate

- filmmaking

- miscalibration

- kevlar (not even capitalised)

- medbay (again, understandable)

- dingus

- bearcat

- unmatted

- coifed

- glutes

- voicebox

- pitter, but not patter

- blacklight

- taur (once again, understandable)

- hindlegs, but not forelegs

- hindpaw, but not forepaw

- mitosed