When i was a child, old enough to be firmly planted in the UK but young enough that every day outside a school’s walls was magical, my family would sometimes take the train up to visit kin in Scotland. I got the window seat, of course — i still hold that those who genuinely prefer aisle seats are suckers — and as i watched the Northumbrian countryside roll by, the sight of one particular town always held my attention, what seemed to me like some kind of Turneresque utopia by the sea. But we never debarked until Scotland was in sight, and this village thus remained a mystery to me. Some days ago, i decided to rectify that. Welcome to Alnmouth.

Well — i say Alnmouth, and indeed so does the sign at the railway station, a modest and drizzly affair that gets a surprising amount of service due to its prime position on the East Coast Main Line. One thing you must understand about the sign and i is that we are filthy, filthy liars. This is Hipsburn, a teeny-tiny1 village about a mile inland. You can get a bus from here to there, or, indeed, to Alnwick, the other town on the station sign and by far the more prestigious.2 But that would be boring, and i came here to touch grass, not listen to other people’s TikToks at maximum volume, so it’s off along the B1338 i go.

As i approach the roundabout ahead of me i think to myself that i would like to retire in one of these cottages, and maybe die there if my transhumanist sympathies should ever fail me. The village’s last institution before it peters out into the countryside is Alnmouth United FC, who are slumming it down on the ninth step of the football pyramid. I wish them well; my old hometown’s club recently folded and got locked out of their pitch, so it’s good to see the local game alive and well here.

From here things get squelchy. I rest for a moment on the girdered pedestrian footbridge, which clings on for dear life to its Victorian car-carrying counterpart, and gaze inland over the river as it flows downstream and under my hooves. The marshy pastures all around, too salty for crops of human worth, once fed oxen and other beasts of burden, but, in 2006, their flood defences were deliberately breached, rewilding them and creating swathes of estuarine saltmarsh. I’m not holding my breath for otters to show up — they’re crepuscular buggers, and i’ve come in the afternoon — but i do spot a relaxed teal in the grasses. (I’ve always been more of a mammal fan, but it’ll do. Call it a home-team bias.)

I carry on down the “Lovers’ Walk” (a popular term for scenic walkways in the eighteenth century, a sign assures me), wedged between piny hillside and sandy water. This is perhaps not the scenery that England would like to advertise to the world: a cold, grey, winter day, where the nominal path is liquid with mud and the river seems permanently half full. Nonetheless, this part of Northumberland is one of our “National Landscapes” — né·e Areas of National Beauty — and i find it sublime even in the most miserable weather.

As i edge closer to the town, a chorus of tweeting, chirruping birds grows louder and louder. I attribute it to the flock of wigeons across the river, but, passing by the boating club and getting (relatively) further inland, its loudness refuses to fade. Imagine my surprise when it turns out to be the back garden of a holiday cottage!

Back down to shore and through the dunes, now. “Danger: River estuary. No bathing,” complains a sign from the council, which is a shame, because unless i want to backtrack it’d be the only viable way to reach the landmark that dominates Alnmouth’s skyline (to the extent that it has one): Church Hill, a cross-topped hillock ever impending in the distance.3 It is said that it was on this wind-blasted top that, in 684 CE, Saint Cuthbert was elected to be Bishop of Hexham. It is also said that two otters would come and warm Saint Cuthbert’s feet after he had stood in the freezing North Sea and whispered his nightly prayers, and that animals regularly helped him with his housework, so take these things with a grain of salt.

At last, i make it to Alnmouth itself, and i regret that i have little to say about it other than that it is nice. There are many nice places in Northumberland, usually ones not located over a coalfield, and though i find them all pleasant, i confess i sometimes have a hard time telling them apart. I take a short break in a café whose windows, in this weather, make the outside world look like a still life by Mr Magoo. I savour every sip of their hot chocolate. It tastes like the ones grandma used to bring home from Spain. I would have liked to stay longer, but as it is, it will already be dark enough by the time i get back to Newcastle (let alone my actual hometown) that they will be holding candlelit vigils for the slain Iranian protestors by the Monument. So, as one does, i leave for the beach.

The walk over takes me across the manicured grass of the local golf club, who i’m again sure are very nice.4 I hang back from the frothy Atlantic, conscious that touching it will likely freeze my bollocks off5, and focus on the sand beneath my feet, its consistency akin to that of… well, sand. Specifically, it reminds me of the play sand that gets everywhere and which every parent surely regrets ever buying for their child. It is soft enough to sink in my steps, tough enough not to immediately fizzle and flood back into the hole left over. The Dutch call this taai, especially when it comes to the texture of food, and it has always bugged me that there is no decent English equivalent.

Trudging back to the Lovers’ Walk over the estuary flats, i spot something that mystifies me. Gossamer shifting sands, light as silk, sailing and shimmering with the force of the wind. When i go over to stand amidst them, they are so thin that i feel nothing on my ankles but the wind. I imagine myself as a sort of low-rent Lawrence of Arabia.

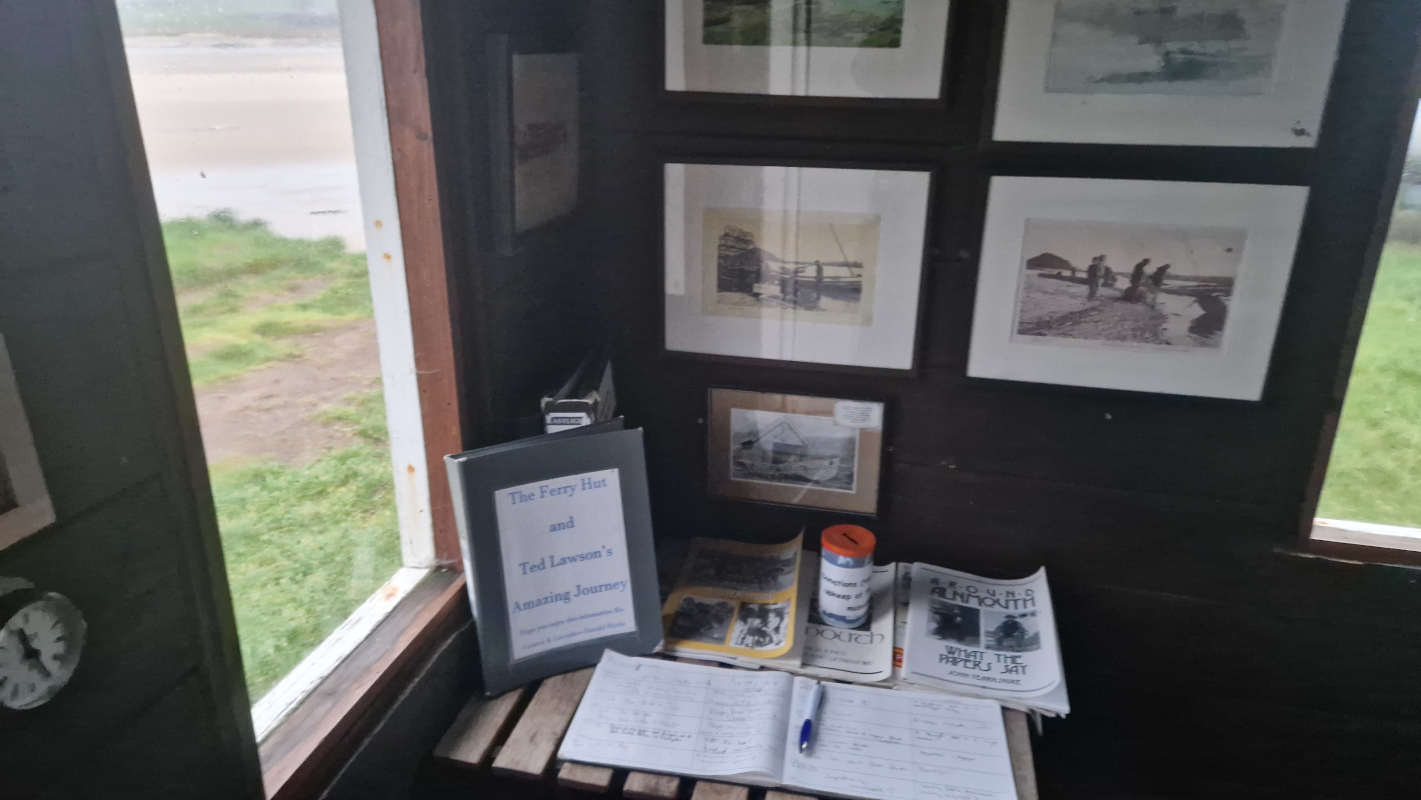

The last place i take note of is a small hut on the land of the boating club. I saw it on the way in, but thought nothing of it at the time, figuring it served some private purpose. But… it’s awfully empty, and there’s noöne around, so… it can’t hurt, can it? I venture towards its nigh-black planks. Crude painted lettering on an old oar over the door calls it the ferry hut; inside, this old shack has been converted into a miniature museum of the village’s history — its people, its ferrymen, how it fared in the war, all told through laminated books and picture frames. I wish i lived in a town that had as much respect for itself as this mere village of five hundred!

Not having brought enough cash for a substantial donation, i settle for a slightly guilty signature in the exhibition’s guestbook, and carry on my merry way home, pleased as punch. I think to myself: I’ll have to come back.

Leave a comment