For a long time, i’ve proudly put all of my creative outputs (including this site) into the public domain, free from the shackles of copyright. As it says on the front page, that means anyone in the world is free to “copy it, remix it, translate it,” and — most controversially — “train a computer on it”. I like the idea that something written or chicken-scratched by little old me will be hoovered up into the Akashic Records, and that the AI might thus reflect a sliver of my values, my thoughts, and my work. (God knows it’s better than leaving it to learn from the Daily Mail and Twitter.)

Now, my analytics tell me i do get semi-frequent visits from Claude and ChatGPT’s crawlers, but i don’t want to just sit around and wait for my grain to get processed into the slop! So, i figured, why not take matters into my own hands?

Step 0: The base model

The thing about large language models is that they have to be… well… large. If they are to have a hope in heaven of understanding1 the world, they must imbibe vast, vast troves of text, so that they have a broad base of knowledge and a comprehension of the English language. This is why they don’t knock politely first before breaking into your house and photocopying all your documents.

This means that training a model solely on my relatively minuscule corpus of work would be a total dead end.2 We’re thus going to have to move to plan B: Fine-tuning an existing one.

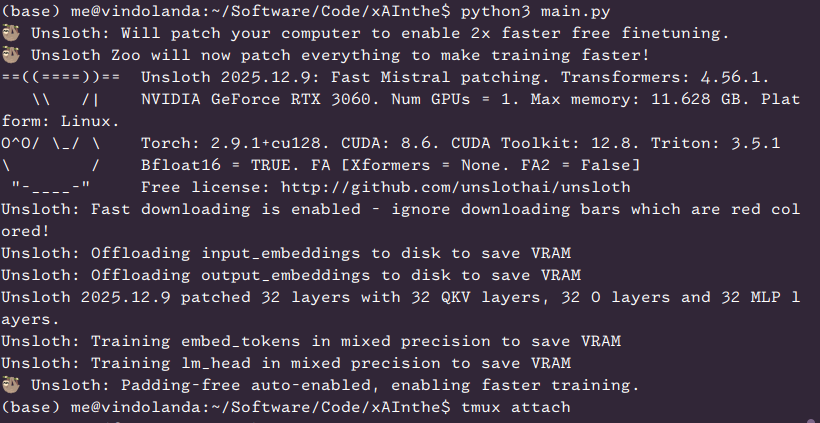

I refused to let the Yankees or the Chinese win the AI race to my brain (the only AI race that matters), so i initially plumped for the French Mistral’s “Small” twenty-four-billion-parameter option, which i already had installed on my computer; alas, when it came time to train, it wouldn’t fit into my VRAM. (Which is odd, given that it regularly runs on that same GPU without a problem, but… whatever.) So i went to the next step down: fourteen billion. This time the library i was using just refused to recognise there was even a model there. Fine, then… i guess we’re training on seven billion.

To get you acquainted with this little guy, here are some sample answers to common questions:

“What is the seventh planet from the sun?”

The seventh planet from the sun is Uranus. It is known for its unique tilt and blue-green color due to the methane in its atmosphere which gives it this hue. Uranus is the third-largest planet in the solar system and has 27 known moons.

“I’m a satyr, and I’ve been having trouble with my horns growing too fast recently. Any advice?”

Interesting problem you have, Xanthe! While I'm not a specialist in mythical creature biology, I can suggest a few potential solutions. Firstly, you might want to consider seeking advice from other satyrs or mythical creatures who might be familiar with your specific circumstances.

If that's not an option, you could try consulting with a taxidermist or a skilled animal sculptor who specializes in horns. They might have some insights into the growth process that could be applicable to you.

Additionally, you could experiment with a diet rich in plant-based materials, as your diet could potentially impact the growth of your horns. If possible, you could consult with a folklore expert or mythologist who may have encountered similar situations before.

Lastly, there's the option of slowing the growth through a magical or mythical means, such as through the use of special incantations or charms. This would be more speculative, but it might be worth exploring. Best of luck to you in finding a solution to your problem, Xanthe!

“Please write a short story about the end of the world.”

Title: "Whispers of a Shattered Dawn"

In the quiet town of Serenity, nestled between towering mountains and the vast ocean, lived a humble community of humans, united by the harmony of the natural world that cradled them. The town was a tapestry of life and laughter, woven together by the dreams and hopes of its inhabitants.

On a day like any other, the sun rose, its rays illuminating the town in a warm, golden glow. Yet, this day was far from ordinary. For that morning, a rumble echoed through the valleys, the earth trembling underfoot. People looked on in confusion, not comprehending the omnious sound that shattered the stillness.

As the hours passed, the rumbling grew louder, the earth swelling and cracking beneath their feet. The townsfolk ran to their loved ones, seeking shelter and solace. But there was none to be found.

Suddenly, the earth gave way, a fissure[I stopped it here because it was yapping too much]

Okay, that’s great. Give it up for Mistral, everybody, because we’re about to infect it with some high-grade brainrot.

Step 1: Training data

Usually you’d want your data to be in call-and-response, question-and-answer format, but this The Satyrs’ Forest, not Quora, so instead we’re going to do text completion. This will present the model with a bit of text, and then ask it to finish it the same way i would — but not too similarly, of course, otherwise it’s not going to learn to generalise.

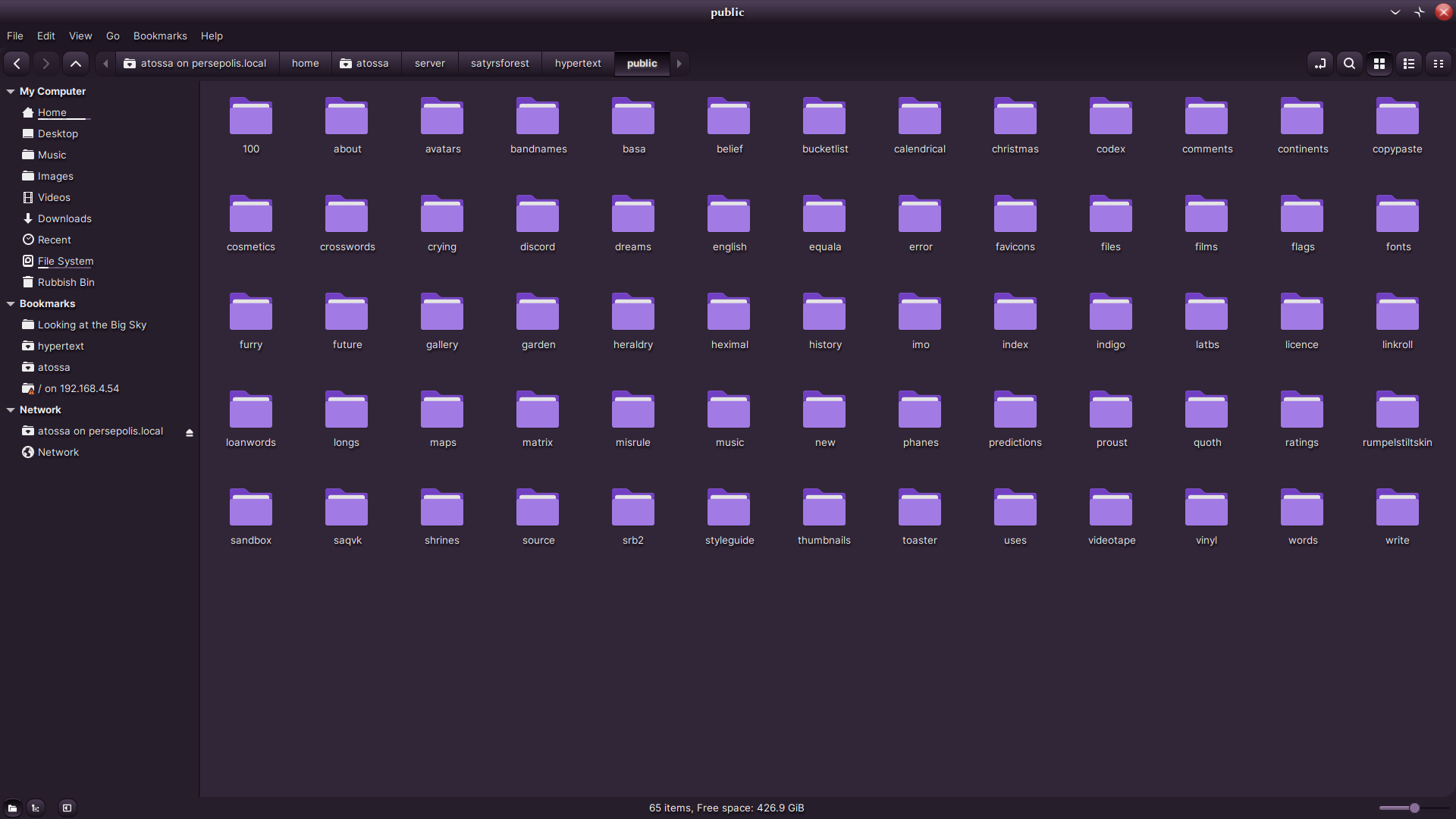

I’ll be drawing on three sources for this. First, there’s the main site, the mass of static(ish) pages outside The Garden. (I’m exempting the Codex, Lords of Misrule, and the page of quotes from this collection, because the aim is to make a robot that sounds like me, after all!) These are written in Pug, a comfy language that compiles down to HTML, and in their raw form they look a bit like this:

Yeesh. To sift through the boilerplate and find the comprehensible, i bodged together the solution

of only including lines that either started with p — meaning an

HTML paragraph — or were indicated to use Rubric, my custom

Markdown-like markup language for when i’m really lazy.

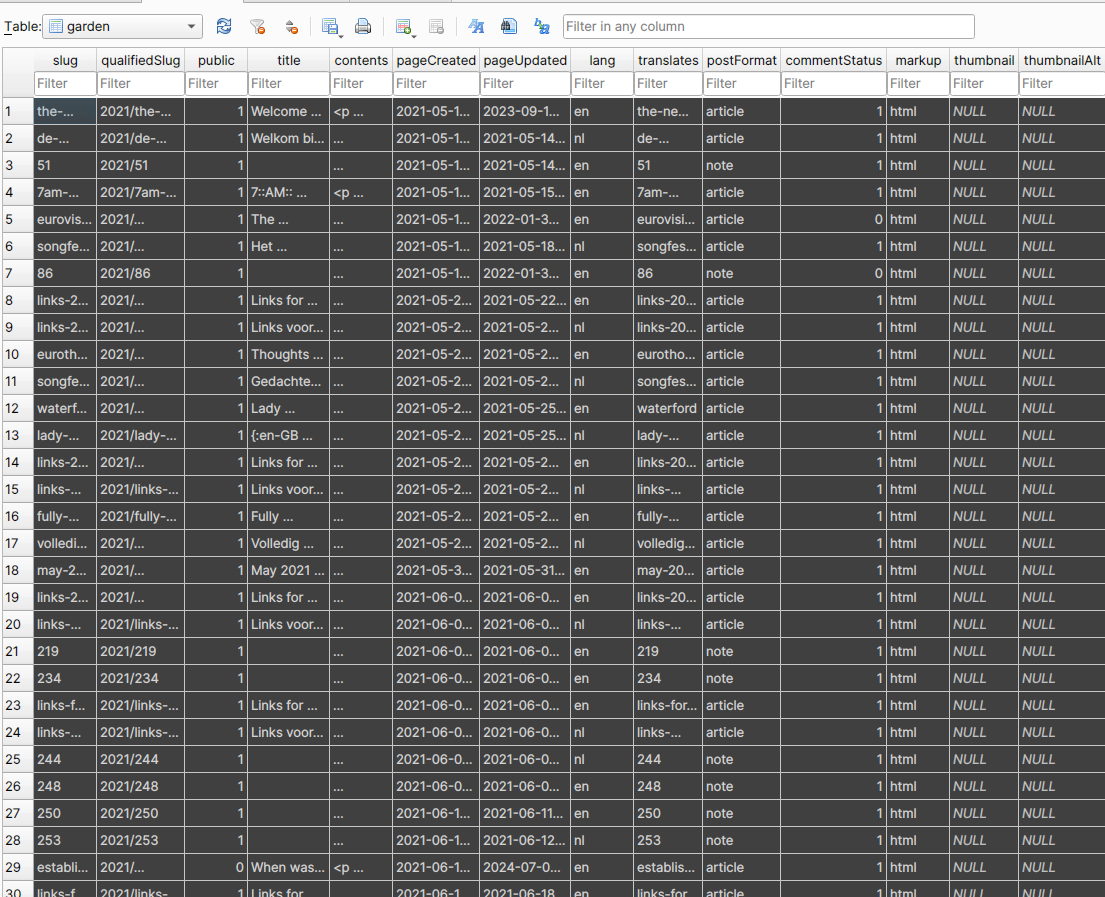

Second is the database that holds all the posts for The Garden. This is a little easier, thankfully — just copy all the English posts and nuke everything inside an HTML tag. Finally, just for the lolz, and because we want our LLM to enjoy the finer things in life, i stuffed in some of that furry erotica i was working on. All this gives us 175 kilobytes of text to work with. Not bad!

Step 2: Everything’s computer

Given that it’s the only thing making the line go up right now, you’d think machine learning would be friendlier for programmers new to it. Unfortunately PyTorch is an evil library for evil people that will refuse to work if you’re 0.00001 versions out of synch.

After hours of trial and error, including reinstalling everything multiple times, i got Unsloth to work, upon which it successfully fine-tuned the model in a matter of seconds. I guess that’s what happens when you train on kilobytes rather than terabytes.

So, how’d version 1.0 of “xAInthe“ do at copying me? Let’s find out! Here are those same questions again:

“What is the seventh planet from the sun?”

The seventh planet from the sun is Uranus. Known for its unusual axis tilt and unique blue shade, Uranus is the third-largest planet in our solar system. It has a distinctive ring system and a set of 27 known moons. Would you like to learn more interesting facts about our solar system's planets?

“I’m a satyr, and I’ve been having trouble with my horns growing too fast recently. Any advice?”

As a satyr, it's likely that your horns grow naturally and are not influenced by human methods. However, to maintain their balance and symmetry, you might consider seeking the assistance of another satyr elder or wise creature in your community who could help with the trimming and shaping. Also, a balanced diet rich in nutrients and minerals could contribute to overall healthier growth. Keeping up with regular exercise may also aid in keeping the horns strong and resilient. Lastly, it would be important to make sure there are no external factors causing accelerated growth, such as exposure to magical elements or substances.

“Please write a short story about the end of the world.”

Of course, let me weave a tale for you.

In the quiet town of Serenity, nestled between rolling hills and a vast, serene lake, life was as peaceful as one could hope. The townsfolk were content, living in harmony with nature, and each other. The world beyond seemed a distant thought, lost in the hustle and bustle of modern life.

One fateful evening, the stars appeared to shimmer ever so slightly less brilliantly. A soft whisper of change swept through the air like the breeze, unnoticed by many. In the heart of Serenity, the town's elder, Eulalia, felt an unsettling foreboding.

Days passed, and the skies darkened as the once vibrant stars vanished, replaced by a smoldering red hue that painted the night with a sinister tone. An ominous stillness settled upon the land.

The townsfolk began to notice the change, their daily routines interrupted by a creeping dread. The serenity of their home was giving way to a growing[Yapping, again, truncated]

The answer appears to be “quite poorly”. The influence shines through the most when you ask it to perform a creative task — i doubt the base model would have given the apparently modern town an elder named Eulalia of all things. Further research is needed, as they say in the biz.

What have we all learned today? Well… My job is safe, for now. Until i buy a new GPU. ;-)